Viola Leddi: Dear Hateful Spirits

Duration: April 3 - May 18, 2025

Text by: Stella Succi

Location: TAG Art Museum, No. 1111 Yinshatan Road, West Coast New District, Qingdao, China

--> Click here for the video of the exhibition <-- Producer: Meng Xianwei; Music: Ólafur Arnalds - TREE; Edited by: Betty XU from TAG team

You have lunch at your parents’ house. You need to write a note, one of those things you jot down on a scrap of paper to avoid keeping it in mind. You ask for a pen. They tell you to check the second drawer. And there it is, perfectly intact, like a prehistoric insect trapped in amber: your old pencil case. You feel nothing in particular—until you touch it. Then, suddenly, the unmistakable resistance of its zipper as you try to open it, the peculiar scent of rubber, worn graphite, sharpened wood, and the faint stains where markers have bled.

You pick up the sharpener between thumb and forefinger, with an absentminded gesture used for objects that have long since lost significance. Without any deliberate intention, you bring the hole to your eye. What do you expect to see? Nothing, of course. And yet, at the bottom of that hole, a room opens. If you move, you can explore it.

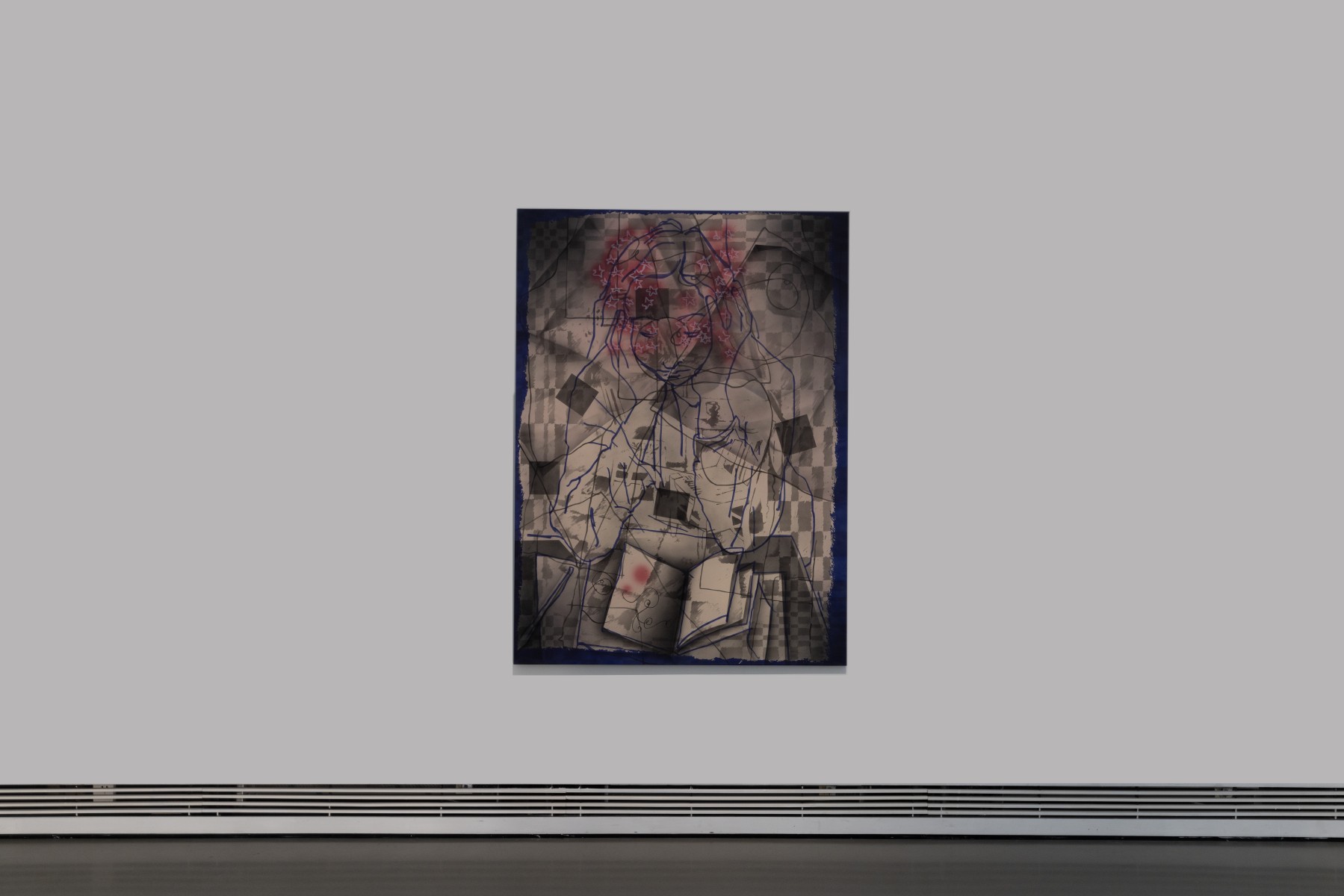

The vision is incomplete, but you recognize the scratched parquet of your teenage bedroom—after all, you were the one who scratched it. They used to tell you not to drag furniture across the floor, to keep it from getting ruined, so you dragged it harder. You leaned your chest over the top of your metal chair’s backrest, gripped the underside of the seat, and began rocking back and forth on the rear legs, marking the floor with careless strokes. You keep looking around, walking, but instinctively, your gaze drops downward, and you realize how much your life, in that moment, was bound to the floor. You think you recognize your old notebooks, the dedications from forgotten friends (but are they truly forgotten? And why them, of all people, and not others?). And there you are as well, a book open on your knees, legs folded in that posture of unfocused concentration that once belonged to you.

Memory is not a repository, nor an archive, nor anything so reassuring. If anything, it is an investigation without method, built on uncertain evidence, fading traces, overlapping and dissolving details. The crime, after all, is everywhere: when one is young, every word spoken or endured carries the weight of a murder. In crime reports involving adolescents, they search the drawers for the ultimate proof—among hearts and glitter, the secret diary.

Youthful writing is not confession, nor even testimony, but an exercise in interpretation conducted with makeshift materials—borrowed phrases, overheard words, impressions still too raw, the attempt to make sense of something that resists being seen from a distance. There is no time, no measure, no reassuring sedimentation; it is a tapestry observed too closely, where one sees the threads but not the pattern. At times, it is an attempt to reclaim a surface already inscribed by others, from the outside. It is an uneven struggle where writing is centered around a void, it’s all skin, porous, and unable to afford the luxury of nostalgia.

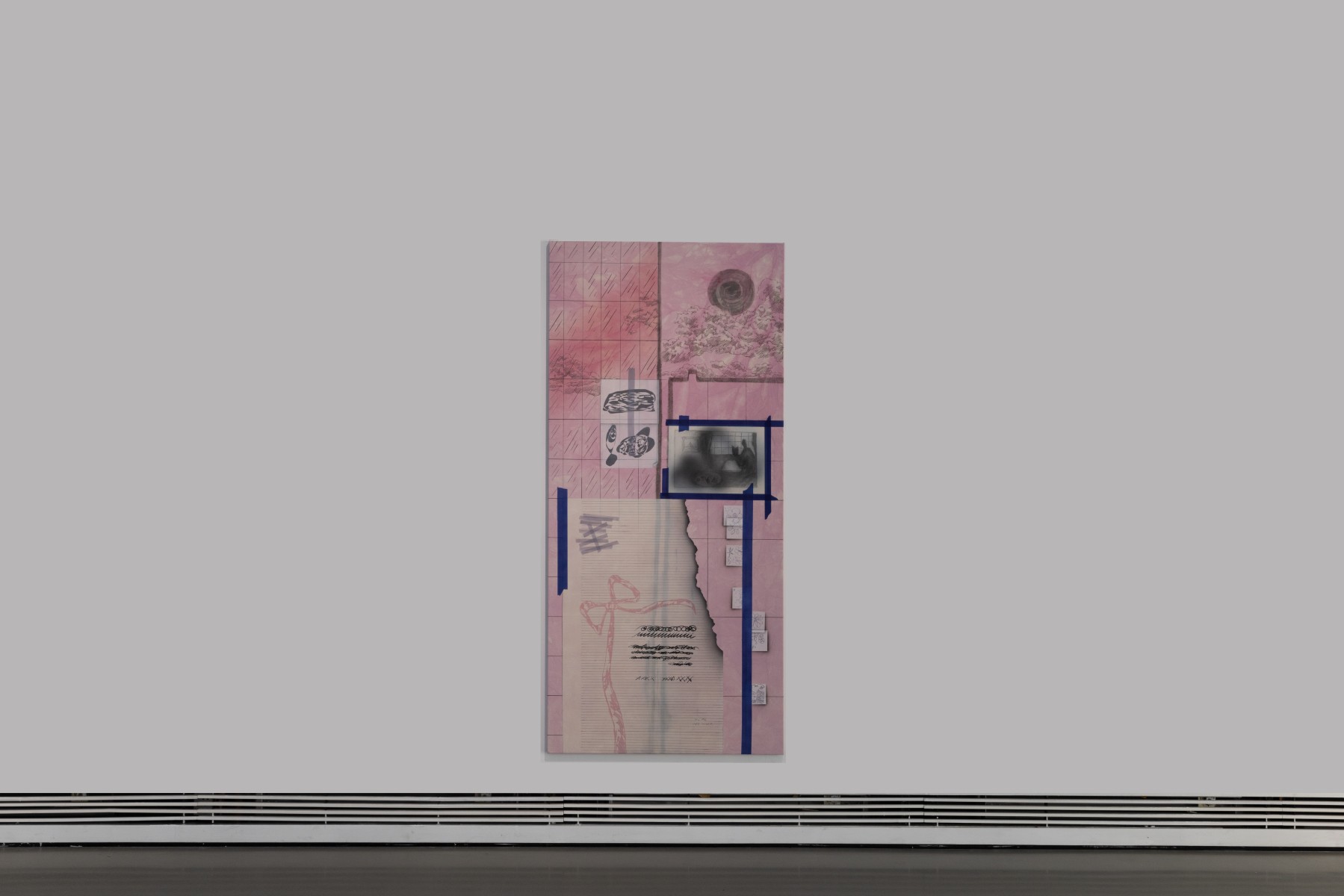

Time capsules are sealed with the intention of preserving history and meaning, sometimes buried underground or cast into space. But what truly reaches the future? Misplaced objects, incomplete notes, inexplicable relics, symbols, and rules. If all that survived of an era were a single room—a room like this—what could posterity ever conclude? How much can be deduced when everything is missing? But there’s only one way to remember: by omission, subtraction, and absence.

You pull the sharpener away from your eye, slip your little finger inside, and turn.

- Stella Succi